Get to Know Each Other is a play but also part of a wider social programme that includes group psychological support.

Beirut, Lebanon – The audience burst into laughter – and nearly burst into tears – as 18 youth and young adults from around Lebanon shared their life stories and struggles with identity, sectarianism, racism, and social marginalisation.

It was the story of a young Druze man who was bullied because he was poor, a Syrian-Lebanese woman born and bred in Beirut struggling with the country’s discriminatory nationality law, a Sunni man from Tripoli raised in a Shia orphanage on the outskirts of the capital for 14 years without ever knowing his identity – and more.

“After the Tayouneh clashes, the increasing friction and polarisation and hatred – working on the ground is important, but sometimes you need a tool that sends a message,” Baroudi tells Al Jazeera.

The play is part of a wider social programme, and includes group psychological support. Baroudi and MARCH Lebanon for a decade have worked on a variety of community-building and conflict-resolution projects in Tripoli and the capital Beirut.

The performances took place in Beirut’s Sunflower Theater, right by the Tayouneh roundabout where armed clashes between Christian Lebanese affiliates and Shia parties Hezbollah and Amal took place last October.

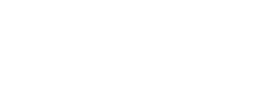

“I was hesitant at first, but after meeting Yehia Jaber and Lea Baroudi, I decided to go for it,” 31-year-old Ibrahim Nazha tells Al Jazeera. The tattoo artist and aspiring rapper was the eldest among the actors, all of whom never acted on stage before.

Aspiring rapper Ibrahim Nazha says people spewed racist comments at him because his mother was from Liberia [Courtesy: Youssef Itani/MARCH]

Aspiring rapper Ibrahim Nazha says people spewed racist comments at him because his mother was from Liberia [Courtesy: Youssef Itani/MARCH]Nazha shared his story about how he experienced racism in his native Baalbek, because his mother was from Liberia. “They would call me ‘coal’,” he told the audience.

The actors high-fived and embraced one another after another fully booked performance, but both Baroudi and Nazha say it took a while to reach that point.

“Even the youth involved in the play were not all in this mindset in the beginning,” Baroudi admits. “Some people wanted to stop, and there were arguments.”

Nazha originally doubted the play would amount to anything.

“At first, I felt I was neglecting my family, and I wasn’t sure if this play will mean anything,” Nazha says, admitting the long rehearsals and time commitment drained him. “But something kept bringing me back.”

Lebanon at a ‘turning point’

Baroudi says Lebanon has been “cantonized” since the end of the civil war in 1990, deepening existing societal divisions based on sect, religion, and even region. The country did implement a reconciliation process, as most of the combatants from the war remain among Lebanon’s most influential political leaders, with huge stakes in the economy.

Almost all the performers were born over a decade after the civil war ended, but still reel from deep societal divisions.

“I’m convinced that we’re at a turning point for Lebanon,” Baroudi says. “People say the problems are corruption, the political class, [no] independence of the judiciary – but for me, there are underlying problems that are the reasons behind all of them.”

Lebanon continues to suffer from a crippling two-year economic crisis that has pushed more than three-quarters of the population into poverty. The Lebanese pound has lost about 90 percent of its value, and hundreds of thousands of Lebanese families now need humanitarian aid.

Baroudi says the country will never recover without people breaking these divides and building ties based on their common experiences.

Nazha echoes similar sentiments and says he hopes the play will inspire people to set aside preconceived notions of the other.

“Everyone is from a different sect or region, but we’re all going through the same thing,” Nazha says. “We’re all human at the end of the day.”